« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

June 7, 2022

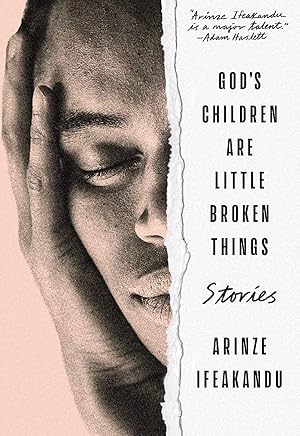

Arinze Ifeakandu's Playlist for His Story Collection "God's Children Are Little Broken Things"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Jesmyn Ward, Lauren Groff, Bret Easton Ellis, Celeste Ng, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Roxane Gay, and many others.

Arinze Ifeakandu's collection God's Children Are Little Broken Things shares heartbreaking and exquisitely told stories of queer love in Nigeria.

Kirkus wrote of the book:

"Nothing less than breathtaking and daring…these tales bear the emotional weight and complexity of novels, with the reader pulled forward by lucid prose and excellent pacing. Most compelling, though, are the unforgettable characters and the relationships that hurl them into the unknown and dangerous depths of their desires."

In his own words, here is Arinze Ifeakandu's Book Notes music playlist for his story collection God's Children Are Little Broken Things:

What is a good song, if not an anthem to help us through life? Like a friend holding our hands, saying, “I know what you’ve been through, cry on me,” or, “I am happy for you, come dance with me.” These songs helped me through the years as I wrote this book, sometimes playing in the background, or into my ears, giving me mood and vibe.

‘Tonight,’ Nonso Amadi

The story, “Alobam” is about, among many other things, night and all the things it forces us to feel. This song was among a few on repeat around the time of writing that story, a particularly fraught time—back home, #ENDSARS, a protest for our very lives, young Nigerians powering the biggest revolution in recent years. Hope and love in the air. It was vulnerable times, too, and this song captured perfectly the feeling. “Tonight, just go all the way with me,” Nonso sings, and what is more vulnerable than asking? The girl, his muse, is “Bright like electric bulb.” I see it immediately, and I hear it, in the slow melancholic beat, the chill, understated drum. Our guy is earnest, “I don’t mind being the number two,” but cool—and why not, when he’s “the boy with the money” who “lives fast,” and has “a special place to help you remember me.” Bars & vibe.

‘Lamentations of Jeremiah I&II,’ Thomas Tallis

The feeling is rapture and reverence. “In terra”, the tenors sigh, “In terra”, the altos respond, a more plaintive sigh, and so it is bounced around, phrase to phrase, charged chord to charged chord, a fired ball of crescendos and diminuendos. The effect: contemplation, quiet anticipation. My heart wrecked by these simple maneuvers. I think of the history of the times, of Thomas Tallis, a closet Catholic in the employ of the reformed Anglican court. England on fire: Catholics are being burnt on a stakes everywhere. I imagine secret cloisters swollen with this sad, pious song. Imagine Tallis at his harpsichord, writing it, his head full of the sound, his heart with the sorrow of longing, the weight of compromise. I sigh with understanding.

“You’re Beautiful” & “Goodbye My Lover,” James Blunt

I think of B. whenever I hear this song. He hurt me terribly. I was 18 and in first year, he was 23, a second year at Nsukka. He was cute and bright, the heartthrob of the English

Department, and liked thick socks at home and gulped sachets of raw Nescafe coffee at night, head bowed over Heidegger. He also liked James Blunt, the Gregorian, Formalism, the Mass said in Latin., and had a jumping gait, and a lying, scheming heart. One night, after I’d texted him saying I was sad (I’d had a long argument with my homophobic roommates), he came around midnight and woke me up. We went to the balcony and he told me he loved me and wanted to see me happy. Before that night, I saw him purely as a friend, but afterwards he became more, even though he had a girlfriend who, like me, was a child. I liked her. He would make dinners in his room of six boys, waking me up to eat when it was ready, giving me massages, waking me up in the middle of night to study. Told me songs to listen to, two of which were these by James Blunt. His roommates called me his boyfriend, in jest—and (unacknowledged) knowing?—and, whenever I slept over, did not fight to keep their mattresses in that coveted corner by the wall. “Leave am for B. and him boyfriend,” they joked. That semester, my first, I nearly made all A’s. He wanted to be my first in everything but he wanted to fuck without a condom and I did not want that, and so, come second semester, after I’d gone home and let someone else be my first, he became different. “You have changed,” he said to me often, disapproving. He gave me his presence as reward, his absence as punishment, cruelly inconsistent. I cried a lot in those days, confused. Whenever I decided to cease all communication with him, he came to me, saying, “So we cannot be friends? That’s unfair, you know I love you.” Pursued me until I was back in his arms, until he was giving and not-giving, inviting girls over to kiss them in my presence, my anguish his pleasure. When James Blunt said, “I’m so hollow,” I felt it in my spirit and my soul. He wanted me to write about him, a power move, I suspected, and so I swore I would never write about him, because doing that would be letting him win. But life is not a game. I named a beloved dog in my collection after him, a decision I made because I loved his name, B., because, for some reason, I continued to talk to him many years after—I was grown, after all, and I knew him for who he was, and he could no longer

hurt me. And then the conversation in Lagos happened, a conversation that dug up something I’d long forgotten, my brain having kept the memory of pleasure while shelving away the humiliation. And so I changed my beloved dog’s name, because I am, after all, the one who tells the stories: I decide what to tell, and how, and when. “It’s time to know the truth,” James Blunt sings. In my message ending all communication with him last November, I said, “I take the pleasure and give you back your humiliation…You have nothing to offer me at this point in my life.” As I blocked him on all social media, I felt the blessedness of power, felt light and free, and ready for love.

“My Heart Is Open,” Maroon 5 ft. Gwen Stefani

I cried a lot listening to this song, tingling with a desire to be loved. I imagined a boy holding out his hands to me, calling me forth, asking me, choosing me. Now, when I listen to it, I am the boy in the mirror of my mind, the arms outstretched mine, open heart, saying, ‘Arinze, “let me hear you say yeah”.’ And if there are tears, they are happy tears, because the answer is yes. Yes, boy, yes I love you, too.

‘Adore,’ Miley Cyrus

It was the use of that one word, that exclamation, “boy.” I didn’t have to edit, to switch pronouns as I sang along. Miley was already singing it for me, with feeling, and when I joined her, Boy, I adore you, it felt true, a song for me. And my heart melted with sweetness.

“Ave Verum,” William Byrd

I especially love the recording by The Sixteen, conducted by Harry Christophers. I stood a lot in front of the mirror as I listened to this, conducting an invisible choir, my moves cursive and expansive. Or waved my hands between sentences as it played in the background while I wrote. I thought of gently undulating waves, heard, in the ever-rolling notes, a plea as the choir sang, “Miserere.” And when they sang, “O Jesu,” there was feeling in the crescendo, like a heart welling, closing into a diminuendo on “Maria,” that phrase sung with gentleness, the way you would call the name of someone you cared about.

‘So Beautiful,’ Asa

This is a love song from a child to her mother. When, at 18, I began writing the short story, “God’s Children Are Little Broken Things,” I was afraid my mother would die. Nothing in reality pointed to this possibility, not concretely. But my grandmother, her mum, had died suddenly after all her sacrifices, a woman who had nine children, a woman who—having been denied education beyond primary school on account of being a girl—swore that all her children would attend university, a dream she accomplished against great odds, having sent several of my uncles and aunties to university before her death at fifty-three. I was her purse, and she called me her archbishop. I was ten when she passed, away at boarding school, and for months I saw her in my dreams, decked in celestial whites. In chapel, I gave testimonies about her, my Mma who was in heaven, and when I cried, there was the consolation that I would see her again someday. She was convener of our large extended family, uniting lost cousins, seeking fleeing wives and bringing them back into the family after the death of their husbands. Our Great Matriarch. When, at 13, I read The Joys of Motherhood, I saw all her works in full light, and understood that the world was unfair to women. And so I feared for my own mother, my kind, loving, wonderfully brave mother. This song is split in two feelings: melancholy and celebration, the verses slow and somber, guitar strumming, drum one beat at a time. In church, we would call it a Worship Song for its air of reverence. The chorus leaps into frenzy, drums escalating, and you go from quietly nodding to dancing. We would call it Praise Time. A fitting juxtaposition, for I feel, these days, that Life is possible, all my fears expunged; that through our collective acts of care, life is possible.

‘Mad Over You,’ Runtown

This is a celebration of all things fun. So open, so unafraid in its declarations, its adoration of the subject of love, or lust, whose dancing body is full of fire, a “superwoman.” He is wooing her, and does not hold back, does not hide: “If I sing for you o, you go love me nonstop / I will love you nonstop” and, “If she follow me go, na enjoyment go kill am o.” A truly dazzling promise.

“A Thousand Years,” Christina Perri

I was writing a story about a young woman who returns home after her father’s death to his long-time boyfriend, and this song was on repeat. The quietness, the pureness of that love: “Darling, don’t be afraid.” The everlastingness: “I’ve loved you for a thousand years / I’ll love you for a thousand more.” Love strong as death.

“All of Me,” John Legend

This was on everybody’s lips, on every radio, in 2013, as I wrote “God’s Children Are Little Broken Things,” Kamsi and Lotanna’s story. It is a mature love he sings of. Unrestrained. No games involved. He is giving his all and she is giving her all. Heads under water yet unafraid. She is a person: perfection, imperfection, he loves it all. Love given and received in full measure.

“Damn,” Omah Lay

I am 25 when I hear this. Life is real. I used to dream of love, now I dream only of revenge. The sky in Iowa makes me sad. Constantly sad. The boy in me is dying, a man emerging, and I do not know this man; no, not yet. I stay alone in my room; humans are exhausting, and men are the worst of humans. I want no man near me, and when I let one near, I do not want to know his story, nor he mine. It is a feature of the city, this loneliness. I miss home, where it is easy, where we say, “Baby” and “nna” and “fine boy” instead of “yo” and “sup.” I write “Alobam” and “Happy Is A Doing Word.” I need to be held. It’s been three years since I last hugged a child. I call Otosirieze at 2 am, my room darkly blue, and he listens quietly as I cry over the phone. “I am tired,” I say. “I am so tired.” I have always felt waves of sadness, but never this—this loss of self. On WhatsApp, Israel asks, “How are you?” and I say I am not fine, and as we talk, Omah Lay sings in the background, “She loves me when I’m drunk, she loves me when I’m jobless, she loves me when I’m lost, even when I no need love, yeah.”

“You are my nigga for life,” Israel says at the end of our chat, and for a moment, all storm is calm.

“Let It Go,” James Bay

This song was on repeat in 2018 as I wrote “What the Singers Say About Love,” a story about a young musician and his great love. I listened to it as I walked home from work, or from my friend’s; listened to it at my writing desk. A song about endings, rendered with heart, it makes me think of that man, every bar knows him, seated at alone until the waiter comes and says it’s time to close up, the bar now empty. Such is the sadness. But it is a beautiful sadness, the sort that comes after you have made a difficult decision in your best interest. “I used to recognize myself,” James Bay sings, and he is not okay with this: “When we’re becoming something else, I think it’s time to walk away.” Yes, the memories are beautiful (“From walking home and talking love”; “From throwing clothes across the floor”), and he does not turn away from them. He accepts everything that used to be, but maintains that an ending is best. May we never look and find ourselves lost in our love for another, and when we do, may we find strength to walk away.

Arinze Ifeakandu was born in Kano, Nigeria, and currently lives in Tallahassee, Florida. An AKO Caine Prize for African Writing finalist and A Public Space Writing Fellow, he is a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop. His work has appeared in A Public Space, Guernica, the Kenyon Review, One Story, and Redemption Song and Other Stories: The Caine Prize for African Writing 2018. God's Children Are Little Broken Things is his first book.

If you appreciate the work that goes into Largehearted Boy, please consider making a donation.